Let’s face it: lawyers have a pretty spotty track record where innovation is concerned. We tend toward the secure, the risk-free, the known…the precedential. We shy from things we view as risky. “New” means “untested” and “untested” means “fraught.” And fraught is a nonstarter.

This propensity toward risk aversion arguably serves our clients reasonably well in the actual delivery of legal services. But it is a two-edged sword. It can simultaneously cripple us and our ability to reimagine how we practice law or how we build our law businesses to meet our clients’ ever-evolving needs.

Enter “design thinking.” Since (roughly) the early 2000s, design has infiltrated business strategy and snowballed into a pretty buzzy topic, both in the broader economy as a whole and—on the edges, anyway—the legal industry in particular. We probably have Steve Jobs and Harvard Business Review to thank for much of that. Even Airbnb is in on the game.

Apple’s long run of atmospheric success is married, they say, to its relentless idolization of simple, functional, and beautiful design. That is, Apple embraced design (and with it, “design thinking”), and that embrace is said to have catapulted the brand into the exosphere.

Here is (one of) law’s dirty little secrets: you have already designed how you deliver legal services. Problem is, you, like most of us, did it poorly. And that’s because most of us didn’t do it intentionally. So most of our clients suffer through an accidentally-mediocre user experience. That’s a shame. And, sadly, it has taken decades for design thinking to infiltrate the business of law. But it is finally here.

What is Design Thinking?

Design thinking is an ethos. An ideology. A worldview. It is also, ultimately, a perfectly replicable process aimed at applying long-established and fundamental design principles to the way we build businesses and the processes in them. It is a hands-on, user-focused way to relentlessly and incrementally innovate, sympathize, humanize, solve problems, and resolve issues. For our purposes, design thinking is how you intentionally craft your law business over time to deliver legal services simply, functionally, and beautifully.

Design thinking’s different adherents disagree slightly on its aesthetics, but virtually all agree that it is a systematic approach to innovation and problem-solving that is, fundamentally:

- user-centered;

- experimental;

- responsive;

- intentional; and

- tolerant of failure.

If that almost burst an aneurysm deep in the recesses of your ample mind, rest assured that you are not alone.

Design thinking and law firms have traditionally gone together like Nutella and moderation. That’s paradoxical, though. Creative problem-solving falls squarely in a lawyer’s wheelhouse. So what happened?

Well, lawyers have largely abandoned problem-solving for their businesses and tend to set their myopic gazes instead only on the more predictable exercise of problem-solving for their clients. What is more, lawyers have an acquired tendency to seek perfection before releasing a project into the wild. That, of course, breeds a bias against action, creativity, curiosity, testing, iteration, and active learning. The results, at least according to the General Counsel at IDEO, Rochael Soper Adranly, are grave:

Ouch.

What would it look like, though, if the bias was instead toward action, and what if lawyers instead chose to carefully, precisely, and without prejudgment identify their customers’ pain points in working with them?

What would it look like if they then strove to systematically (and incrementally) design an experience for their clients that is—gloriously and intentionally and precisely—free from those moments of friction?

What if they were able to deeply and personally empathize with what their clients want? What if they offered a modern web presence, fixed fees, collaboration and inclusion in the process, excellent customer service, and an onboarding experience that knocks every single customer’s socks off?

Here’s a hypothesis: They would unearth earth-shatteringly delightful experiences for their lawyers, their staff, and their clients alike.

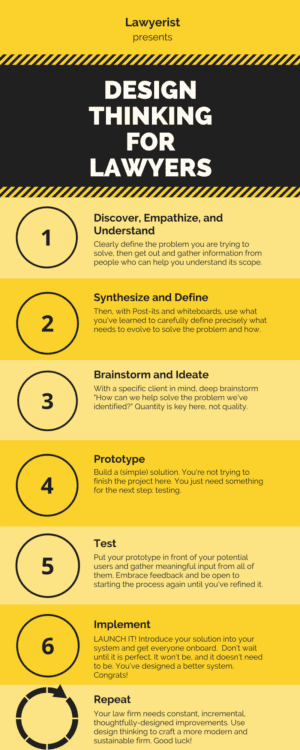

A Six-Step Design Thinking Process.

The design thinking process is often described variously as a 3-step, 5-step, or 6-step process (or an iterative circle, or something else). But I like a 6-step process. Sounds simple, right? Well, it isn’t. You should try it anyway. You should pick a problem, complexity, or innovation that could make your clients’ experience with your business better. Then you should:

Step 1: Discover, Empathize, and Understand

At design thinking’s core sits its power to help you discern what your clients truly want and need. We know you’re already giving them great legal advice. That is a utilitarian, traditional value proposition, and it is necessary. But it is no longer sufficient. To unleash the true power of design, you’ll need to surface a user experience that makes your clients feel amazing about the process, too.

In this step, you’ll gather a bunch of information before you start problem-solving. For starters, you need to clearly define the problem you are trying to solve. Empathy is critical here. What motivates your clients? Why do they need or want the end result?

Identify the right people to talk to for your information gathering endeavor. Then set aside your own assumptions. Get out of your office and interview them. Get their perspective, understand their experience and their desires, and unpack your insights. Try to gather and contemplate their emotional responses—and, secondarily, their rational ones—to your brand. Next, you’ll define your project’s scope and its solution from this new-found, non-arbitrary human perspective.

Step 2: Synthesize and Define

Once you have done the work to understand your clients’ emotional experience with your brand, you need to scope your project. What, precisely, are you trying to evolve? This step is really challenging. It usually involves a crate full of Post-it Notes and all of the walls. You’ll make your data from Step 1 visual, get it out of your head, and move it onto paper. Then you can (literally) move ideas and concepts closer or further away from each other. You can physically cluster things around themes and recognize patterns. Question assumptions. And think unflinchingly about your end user and what they want. Then scope your project to meet their desires.

Step 3: Brainstorm and Ideate

This step is when you direct your laser’s focus on who your client is and how you can solve their problem beautifully. With your team, explore the question: “How can we help so-and-so client with the problem that we’ve identified?” Leave it broad enough so there is more than one possible solution. Get these solutions out on the table to consider, but don’t critique them (yet). Your opportunity here is to create an environment where you and your team can escape your comfort zones to reflect, explore, and learn. You’ll need to lead by example to show them that you can change your perceptions and goals. Experiment with brainstorming ideas and methods. (Yep, you can even approach how to brainstorm through the design-thinking lens). Then combine, refine, and augment ideas to find a plethora of possible solutions.

To be sure, some of these ideas will be unmitigated bus fires. But just as surely, some will be kernels of brilliance. So categorize ideas, give them names, and choose the best ones (for now) to move with. Then get some more whiteboards, some more Post-its, and some more mind maps. The goal here is quantity, not quality. Defer judgment. Don’t censor. Build off ideas, and encourage new and wild ones.

Step 4: Prototype

From there, you’ll choose one or (maybe) more ideas to carry forward. Thinking critically about your firm’s capacity for change and your innovation priorities, identify the one (or maybe two) brainstorm ideas you will pursue first. Then build a “prototype” of the solution by spending only as much time, effort, and investment you need to generate useful feedback and help evolve the idea.

Maybe your client onboarding process sucks. And maybe your design-thinking process drove you toward a solution that involves integrating a new TypeForm to capture new client data and a Zapier integration to dump that data into a spreadsheet somewhere. Build the prototype. You could build a blunt (but functional) system like that in an hour or two, including the time it will take you to sign up for your free accounts. Prototyping’s goal is not to finish the project. It is to learn about the solution’s strengths and weaknesses and to identify new directions that future prototypes might take.

Step 5: Test

Now, take your prototype solution back to your potential users and ask them for feedback. Get meaningful input from everyone you can: your team, your clients, your other stakeholders. Find easy ways to try your ideas, then turn an idea into something a user can interact with (your TypeForm, a wall of Post-it Notes, a presentation, a storyboard). And embrace all the feedback you uncover, including the negative.

You’re probably going to find new problems and issues here (which will, gloriously, lead to more iterations and refinements). Would the solution actually work? Does it meet your end-users’ emotional and rational needs? Be rigorous. Failures here are simply more opportunities to learn and progress. Eventually, all this work will bring you inexorably back to the discovery phase, where you’ll start all over again.

Step 6: Implement

Release it into the wild! SHIP IT! Think for a moment about your smartphone and the software that lives on it… if your phone is anything like mine, it downloads and installs updates for 10–15 apps on any given evening. Not infrequently, you can bank on an operating system upgrade, too.

Your law firm needs frequent updates. They can be small improvements on existing systems, or they can be wholesale launches of brand new tools and workflows. If you wait to launch until something is fully baked, you’re doing yourself and your clients a disservice. Like app developers and Apple’s vaunted design team, you should constantly be on the lookout for problems, then regularly fix ’em, iterate, and launch the update. Your first implementation doesn’t need to be the final one (in fact, it shouldn’t be). That’s why you shouldn’t wait to release a “perfect” thing. It is never perfect; there is always room for improvement. Communicate continually to evaluate, learn, innovate, and create, and join in the perpetual loop of design thinking and service upgrades.

In all of this, you’ll challenge yourself (and your team) and you’ll need to trust everyone in the room, including yourself, as a source of incrementally innovative solutions. Be honest, curious, and brave in considering your different options. Take time to do it right. Try multi-disciplinary teams to approach problems and solutions from all angles.

But When?

Historically, companies treated the design function as a downstream step in a product- or service-development workflow. A services provider—or an engineer in R&D—might do innovation’s substantive slog. Then, much later in the process (or, perhaps, never), a designer would finally be invited to put a beautiful wrapper on the thing.

But an effort to simply slap a beautiful wrapper on a crummy product or experience is sloppy at best or–worse and much more likely–completely tone deaf. Instead, lawyers should, relentlessly and incrementally, follow design thinking’s step-by-step process to unearth better ideas for how to meet their clients’ needs and desires before they design it in the first place.

Ultimately, a beautiful and perfectly-designed system that solves the wrong problem will crumble. And a process that solves the right problem with a terribly-designed experience will almost certainly share a similar fate.

Why Design Thinking?

Lawyers use design thinking because it is the most powerful tool we know to help them innovate in manageable ways. It helps lawyers step back and re-envision their accidentally-mediocre service delivery design using a client-centered process. That process starts with user data, creates or upgrades systems, tools, and processes that address real (not imaginary) needs, then provides a framework to test prototypes and launch solutions with real users. Design thinking creates leverage for your firm’s collective experience and expertise. And it establishes shared language and buy-in on the new innovations from your team.

Perhaps most importantly, design thinking encourages innovation by encouraging your whole team to systematically uncover many ways to fix the same problem.

How Do Lawyers “Do” Design Thinking?

What’s next? How do you even begin? First, don’t be scared off by your fears that to “do” design thinking, you need to go all in at first. Sure, effective design thinking has the potential to become an iterative, cyclical, culture-changing force in your life and business. But the key to any innovation is to start small.

So, start small. Set a goal to work through a design thinking cycle for one small problem this quarter. It is going to be clumsy and slow and uncomfortable at first. Be patient with yourself and your team, because this can definitely feel like chaos if you’re doing it for the first time.

Make sure you explicitly structure your process. If you have a team—and you plan to have its members join you on this maiden voyage—communicate your structure to them, together with your expectations for communication, collaboration, empathy, and iteration. And speak out loud your express directive that everyone involved in the process questions the prevailing orthodoxy.

Next, choose among your products, services, processes, organizational design, or your strategy. Use design thinking to incrementally (but relentlessly) make this one thing better, faster, and easier to deliver.

And as you cycle through and get more comfortable conceptually—as you take the training wheels off—you’ll begin to blend big and small projects and innovations. The beauty of design thinking is that it can be employed for macro innovations and for micro ones.

Fear not the headwinds. Finding, testing, developing, and selling new ideas is hard work for all kinds of reasons. Particularly in organizations. And—even more particularly—in law firms, where long-term, scalable, revenue-driving solutions and services are frequently sacrificed at the altar of short-term profits.

Well-implemented design thinking will create in your entire ecosystem a bias toward action through relentless incrementalism.

You’re on the road to a thorough and genuine understanding of what your clients want and need, and what they like and dislike about the way you have completed, packaged, marketed, sold, and supported a particular product or service. There is power in that. There is power in beginning the journey toward being intentional about how you’re doing all of the things.

A persistent myth about brilliant design is that great ideas are birthed fully formed from transcendent minds in feats of creativity a mere mortal could only dream about.

Leonardo da Vinci is credited with saying that “simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” Simple, beautiful, client-focused design is sophistication that does not spring forth in an explosion. It is cultivated over time through hard work, a supportive environment, a client-centered development process, and iterative cycles of prototyping, testing, and refining, all fed, as always, by relentless incrementalism, curiosity, and a genuine desire to make life better for your clients.

Originally published 2019-07-29. Republished 2019-10-18.

Share Article

Last updated October 7th, 2022